Sometimes a very complex thing can be summarized very easily. Historic Heston is a landmark cookbook, one that may be equaled but that can never be surpassed. Never. It is not your standard cookbook by any means. It does sit in a niche. But if you take time to look into that niche, to explore this book, then you will be amazed.

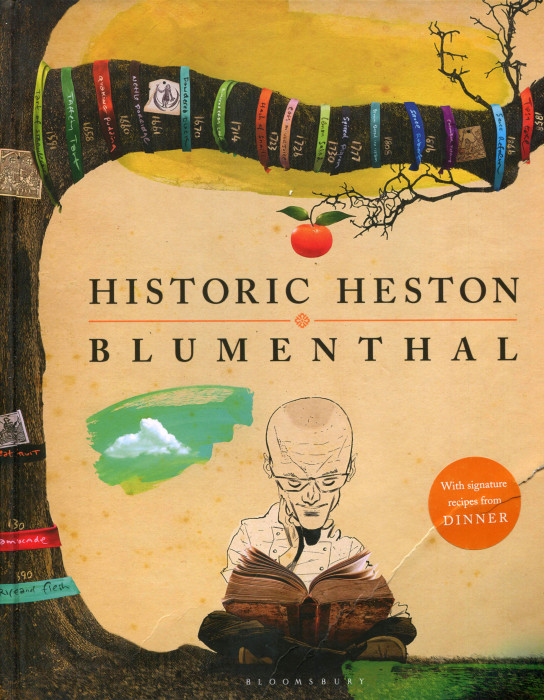

Historic Heston is a complex thing. It is a beautiful thing. And it is a book that you can spend hours reading and be wondrously entertained every minute of your journey. There is wonderful artwork by Dave McKean and superb photography by Romas Foord to entice you from one recipe to the next.

The author, Heston Blumenthal, is as interesting as the book. At sixteen he went on a family holiday to Provence. Eyes opened, he left school at eighteen and embarked on a ten year journey of culinary learning. Where has he ended up? With one of Britain’s four 3-star Michelin restaurants [The Fat Duck], with a kitchen stocked with the lasted culinary space-age gear, and with a passion for history that is remarkable for his capture of detail. He’s a very smart man with very dedicated interests.

If I mention food history, you think of France or Italy or China. Places with centuries and centuries of culinary tradition and evolution. And does Great Britain have a culinary history? Ah, that question can draw sharp barbs or deep chuckles because, until recently, Britain was a culinary desert. Except it was not always that way. Medieval Britain had culinary quality that rivaled France and Italy. Heston explains what happened, what caused the descent into fish and chips, and discusses how he uses those medieval wonders as inspiration for the recipes that appear in this book.

This book is a culinary history, featuring dishes from 1390 all the way to 1892. The dishes here are not duplicated exactly as they once were — and sometimes details are lost so even Heston has no clear path to fashioning the original— but rather they appear as Heston can create them now using all his experience, his staff, and his many gadgets. Medieval kitchens did not have sous vide equipment, but Heston does and he uses that and water baths and thermometers and other gear to take a concept and make a dish alive in a modern sense.

There are 28 recipes here and they each take pages. First there is background and history. Then the recipe for the many components needed for the ultimate dish. These are mostly “high class” dishes, ones that a kitchen staff might have prepared for a royal banquet. So you find “composed” dishes with multiple components: 5, 10, 15 different elements that have to be prepped and then suitably assembled and combined. No, there is no completed dish in this book you can make in 30 minutes. But some of the components you could. And with a few days’ work, and your refrigerator, you can finally have on your table the army of components needed for the final assembly.

Here are some sample dishes from those 28. Just try to guess what they might look like. And, no, don’t be biased by ingredients. Each one of these would, at first taste, make your eyes water in gratitude.

Meat Fruit, a 1430 spectacle that seems to be a Flemish painting

Buttered Crab Loaf

Powdered Duck

Nettle Porridge

Hash of Snails

Ragoo of Pigs Ears

Spiced Pidgeon

I would never put “snails” and “hash” in the same sentence, let alone on top of a plate. But you can, and it works. Well, the picture is so inviting, that I might finally succomb to something snail.

Medieval food, particularly, the more common dishes is often looked down on as simple or stark. Heston goes to length to explain why these dishes existed, why they were made the way they were. For example, at the end of this post is a picture of a soup called Joutes. There were an abundance of religious holidays called for fasting from meat. And even when you were not fasting, you still had to eat a “balanced” diet.

Balanced then meant being respectful of the four bodily fluids were are all composed of [assuming you believe in 15th century science]: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Old men and children were often viewed as phlegmatic and therefore had to avoid lamb, a dish considered moist and cold. Those four bodily fluids? There were also four characteristics of every element and object: dry, cold, hot, and wet. Those four things had to be balanced in every dish, too, so the bodily fluids would stay balanced. Beef was “dry” and therefore had to be boiled to gain moisture. Pork was “moist” and had to be roasted to lose it.

This was kitchen science in medieval times, as well studied and intentioned as today’s research into barbeque sauce.

To make this Joute, you need a few things:

- Vegetable Stock

- Bone Marrow Infusion

- Bone Marrow Royale [gelling the infusion]

- Green Gazpacho Base

- Pea Puree

- Veloute

- Olive Oil Mayonnaise

- Tonic of gazpacho and olive oil mayonnaise

- Pickled Shallots

- Verjus Jelly

- Cheese Slices baked with beer, mustard, and ketchup

- Cheese Toasts

I told you: no 30-minute meals.

Heston describes each of these components and all the steps using a hundred ingredients to create the Joute, a soup for those fasting days. Who knew so much work could go into “simple” fasting? When you see this picture, somehow all those components and ingredients and steps seem less formidable. Who could resist?

If you love food, if you love art, if you love history, and surely if you love all three, then Historic Heston is that one book you would take to your desert island. Along with, of course, your sous vide machine.